Art For The Machines: Part VI – Unpublished Video Games Are Games Too

Gargantuan (N/A) – We naturally have to address this “parallel” chapter during a gradually more and more shaky era for the 8-bit machines. Gargantuan was an unreleased and most definitely very unfinished game of which relatively little is known. It was supposed to come out for both the C64, Amiga, and Atari ST. And the release was probably planned for 1988.

This paragraph is from the Games That Weren’t website: “The game was to be a 12 level scrolling Shoot ‘Em-Up based on the legend of Hercules, where some levels were horizontal scrolling, some vertical, some freeform. All levels however ended with a mid-level boss and big end of level bosses. The main ship expanded with power-ups and multiples, etc. Overall the game was sounding very tasty, and one for the Shoot ‘Em-Up fans… However it was not to be. The game was sadly cancelled after the publisher went out of business, and Denton never managed to sell it to anyone else. This was around the time that both Stuart Fotheringham and Steve Wetherill left Denton. (Steve was behind the game’s design, and coding on the Amiga.) Andreas Wallström has helped to confirm that the coder for the C64 edition was very likely Terry Sanders, and was the last C64 game he worked on.“

We can only speculate around why the hell nobody was interested in publishing the game – A Shmup in 1988 would have moved a couple copies no matter what…?! As for the publisher mentioned (The one that went out of business.) – It could possibly have been Beyond since Infodroid was one of their very last released games. (Palace Software who published Troll lasted until 1991 when they were bought by Titus France.) Steve Wetherill worked on a couple of ZX Spectrum games like Heartland, Sidewize, and Crosswize. He was also one of the coders behind Under Pressure, Projectyle, MYTH: History In The Making, and Desert Strike: Return To The Gulf for the Amiga.

Either way – We’ll probably never see anything “real” from Gargantuan. Which is a hard and cruel shame. — Release: N/A · Credits: (C64) Stuart James Fotheringham / (Amiga) Steve Wetherill · N/A

Quondam (CRASH / Ocean, 1989) – After nearly nine months of more or less deafening silence from “Camp Denton” following Foxx Fights Back!, there was… Still no new game coming… No previews or anything of the sort in the magazines…

But in July 1989, a certain well known mag called CRASH, and issue #66 specifically, featured Batman, James Bond, and Indiana Jones on the cover, as well as an intriguing caption: “4 HOT SPECTRUM GAMES FOR ONLY £1.50!” That’s: “Two unreleased greats and two classics!” These of course came on the issue’s cover tape. Robot Messiah and Whole New Ballgame on Side B, and One Man And His Droid on Side A along with a game called Quondam by… Denton Designs?! Now that’s unexpected…! Just as unexpected that none of the people behind Foxx Fights Back or the latest games had anything to do with it. No – This original and well-designed (Imagine that!) little shooter was created by John Gibson and Karen Davies from the original team… Well, surely it must have been a demo on that cassette? No again – It was the full game. And to publish the entire game was of course an unfathomable welcome initiative from the publication. (Obviously, Ocean wasn’t going to release or market it in any way, shape, or form. On the Speccy, they were more or less all about Coin-Op conversions and movie-licenses at this point. That gold fever must have gotten really bad.) CRASH presented Quondam as “an original CRASH game from Ocean”, though.

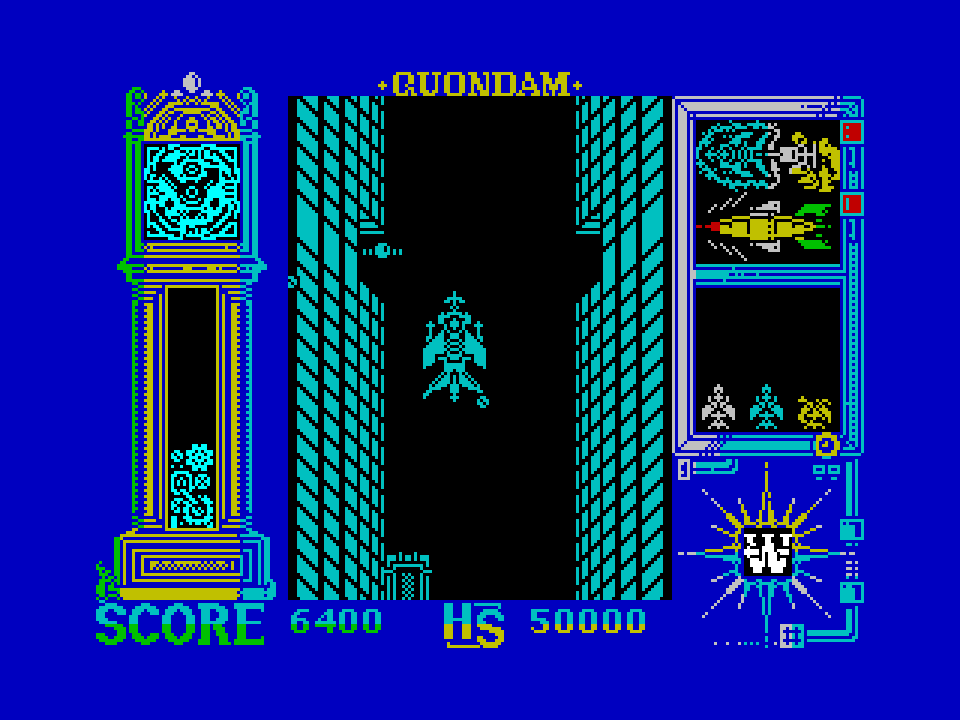

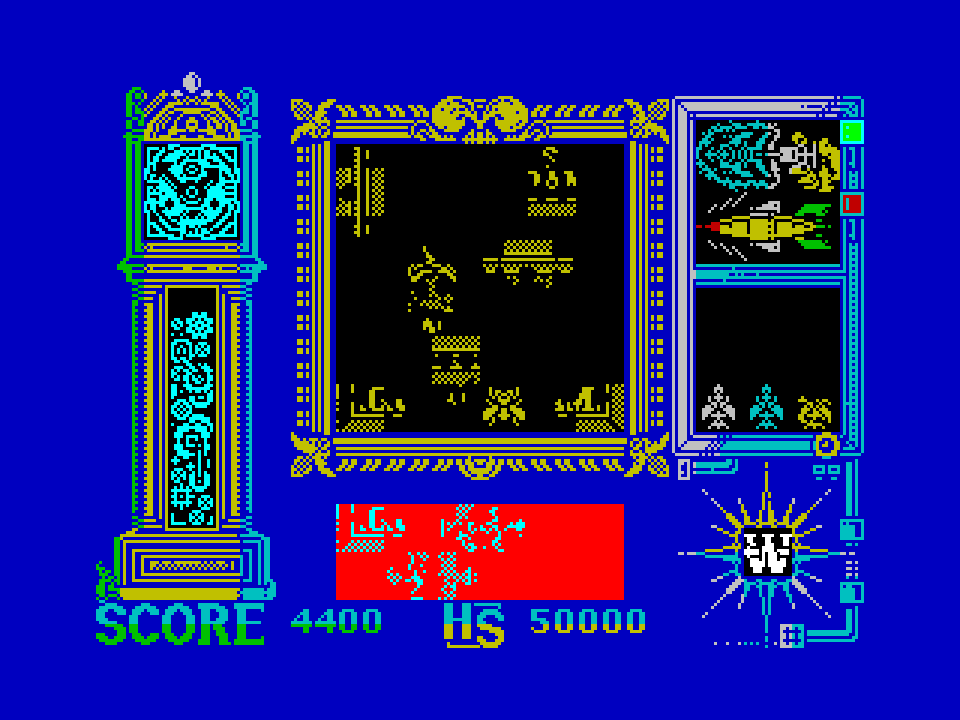

Quondam is a two-way vertically scrolling Shoot ‘Em-Up that takes place around and between 43 city blocks where each one has an hangar. Some of the blocks are quadrangular or rectangular while others are more irregularly shaped. You will be flying your flying machine between the buildings above the streets, and this part of the city is known as the Quondam Matrix. Your mission is to find fifteen unique pieces to a literal jigsaw puzzle. The puzzle itself is accessed by entering the hangars – Simply by flying into them. Once you have located the pieces, you have to piece the jigsaw together on a surface that’s 6×6 slots big. (Inside the hangar.) This surface also has duplicate pieces of the unfinished image. You have to choose which pieces to bring with you, and you only have room for six of them aboard. The pieces also weigh quite a bit, so you lose energy faster the more pieces you fly around with. Inside the hangar, you control a cursor shaped as a fly. (Cosmic Wartoad reference? *sniffle*) This fly has the ability to pick up and move the jigsaw pieces with the help of the Fire-button and the Joystick. To load the ship with pieces, you move and place them on the red rectangle below the image. Additionally, you have to figure out in which hangar to assemble the jigsaw. The other hangars are equipped with invulnerability shields and heat-seeking missiles for your ship to use. Because there will be a lot of blasting above the streets.

Like many ZX Spectrum-games, Quondam begins with the control selection. (There is no “real” title screen, or anything. Although there probably would have been had the game been published as a retail title.) When you press the Fire-button, the interface is displayed, including a piece of the Quondam Matrix map pointing out where you start. (Slamming the Space-bar exits the map and takes you to the game.)

Quondam may immediately look like a very ordinary vertically scrolling 2D Shmup, but it actually has three dimensional movement. Left and right obviously moves the ship left and right and Fire shoots, but then, you can fly faster by pushing the Joystick up. This makes the ship simultaneously descend closer to the ground. Likewise if you push the Joystick down, the ship decelerates and ascends. But when you push the stick down at the ship’s maximal altitude, it turns 180 degrees and starts flying in the opposite direction. (Logically shifting the scrolling direction as well.) At junctions, you have the freedom to fly left or right, but the Matrix always scrolls vertically. So the viewpoint shifts every time you make a 90 degree “turn”. But if you wish to enter a hangar (The entrances are at the bottom of the buildings.), you have to fly directly towards it. You can’t move left or right into it while flying up or down. (If that even makes any sense.)

On the left side of the screen is a grandfather’s clock with a clock face and a vertically moving pillar of cogs. (Where the pendulum usually is.) The clock face pixel-dissolves solves during the course of the 40 real minutes you have to complete the mission. The cogs represent your energy. As your energy fades, the cogs move down and eventually out of view. At the bottom of the screen is the score counter and the current / today’s Hi-score. And on the right side of the screen, you find two icons – One with a ship and one with a missile. These icons have a red / green light next to them. If the ship’s light is green, it’s temporarily invulnerable. If the missile light is green, you have a couple of missiles locked and loaded for your enemies. When the lights flash between red and green, the invulnerability and / or missiles are running out. Red lights on both icons logically mean no shield and no missiles.

Displayed below these icons is a life counter in the shape of three ships (You get an extra life every 10.000 points.), and below that: A compass. (Showing in which direction you are flying – North, east, west, or south.) This is very good for figuring out where you are due to the screen only scrolling upwards or downwards. Pressing the Space-bar brings up a map of your closest surroundings. This map also shows which numbers the hangars have.

Quondam is a nice and very playable, slick and relatively smooth-running shooter that easily could have been a “commercial” game. But this is where Ocean’s wheels started to wobble for real. Because what did Ocean publish in 1989? A couple of compilations. (Five for the Speccy alone!) Everybody’s favorite Red Heat. The Untouchables and Batman – The Movie. And RoboCop for the C64. Sure – Some really top of the line shit. But nothing eye-catching for the Speccy in the shape of a well needed original franchise.

Quondam was incidentally the first Denton-related Spectrum-game that John Gibson worked on since Cosmic Wartoad. Karen Davies’ previous Denton-credit was either Enigma Force or Bounces for the C64. (Both Davies and Gibson worked on Galivan – Cosmo Police for the Speccy, which at least reminds of the Coin-Op original – Unlike the C64-version.)

And always speaking of the C64 – According to the Games That Weren’t web-site, Paul McCarthy and Mike Hutchinson were apparently working on the C64-version of Quondam. And since Jonathan Dunn wrote a tune called “Quandamnation” in 1990, there was a rumor that Dunn was attached to producing the soundtrack. But C64-Quondam shared a similar fate with another game that McCarthy and Hutchinson were porting from the Speccy – Flashpoint… And with that being said, we have reached that very game. — Release: Summer (July) 1989 · Credits: Karen Davies, John Gibson · ZX Spectrum 48K (Cassette)

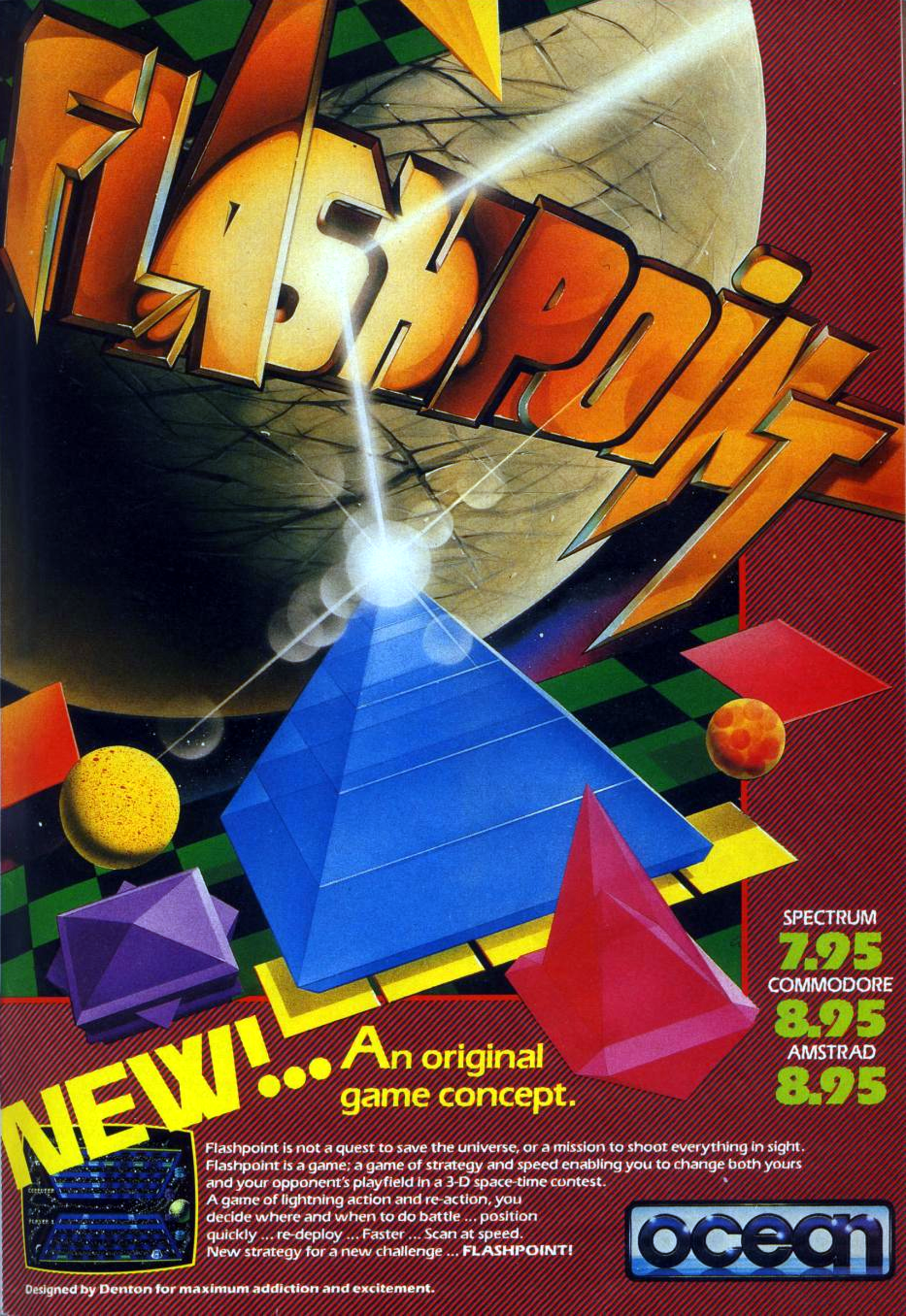

Flashpoint (Your Sinclair / Ocean) – “NEW!.. An original game concept.” said the eye-catching ad for Flashpoint as it appeared in a couple of magazines, e.g., Sinclair User issue #69, in late 1987. “Flashpoint is not a quest to save the universe, or a mission to shoot everything in sight. Flashpoint is a game: a game of strategy and speed enabling you to change both yours and your opponent’s playfield in a 3-D space-time contest. A game of lightning action and re-action, you decide where and when to battle …position quickly …re-deploy …Faster …Scan at speed. New strategy for a new challenge … FLASHPOINT!”

Sinclair User already mentioned this game in July 1987, but if you read between the lines, there were signs that Ocean were seriously losing interest in Denton Designs’ games. (“Streetdate: Not at all sure.”) How else are we going to interpret this whole situation? A good assumption is that it became more and more about the money – Sell a couple of more copies of the latest movie license game or whatever instead of publishing something original… And so Flashpoint remained absent from the market. (The game was also advertised for the C64 and Amstrad, but nothing was released on those machines either.)

“Designed by Denton for maximum addiction and excitement.” So that’s apparently nothing that Ocean would have wanted to release at this point, then? Right. It’s obvious when they, according to the Games That Weren’t web-site, canceled both Flashpoint and another game called Starace. So what the hell were they up to? Games That Weren’t also has a bit on the potential C64-version that more or less was complete. Paul McCarthy created the graphics and Mike Hutchinson programmed the game. (Of Double Dragon II – The Revenge and Jackal fame… Although… He also coded the Super-games Final Fight, Hard Drivin’, HKM – Human Killing Machine, and Line Of Fire… Yeah… It’s no use trying to play the devil’s advocate here…) Fred Gray is credited with a “(?)” regarding the music, but it’s a good estimation that he would have written the music. Anyway. The C64-version is probably lost forever and merely one photograph of a screenshot survived.

But something eventually happened. In November 1989, issue #47 of Your Sinclair was released. And it featured Smash Tape 23 on the cover… And on Side A of the tape: The full version of Flashpoint. (Side B featured a demo of Power Drift with an exclusive level.) Your Sinclair light-heartedly downplayed the fact that the game wasn’t released – By joking that instead of making the game available for people who could afford full-price games, it was a much better move to “circulate it overnight for the créme de la créme of computer users”… Well, no argument there this time…! So here’s the game that Ocean thought was “too cerebral and hard to master”. (That’s what I say too when I can’t play a game or read its fuckin’ instructions.)

Flashpoint’s title screen has a deliriously lovely piece that can’t be anything else than a Fred Gray-tune. (It definitely would have sounded absolutely perfect on the C64!) Here, you select between a one-player game, a two-player ditto, or a “Demonstration Game” where the CPU plays against itself. If you select the one-player mode, you battle the computer. There are four difficulty levels – Practice, Easy, Hard, and Very Hard.

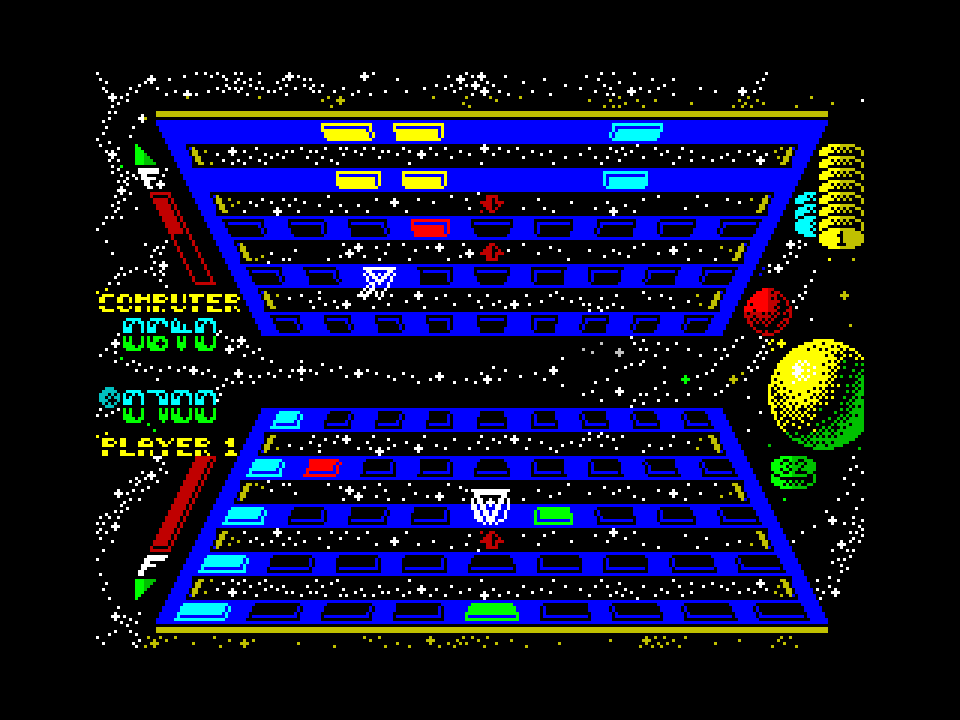

Flashpoint is a real-time, action-based board game that’s played on two independent surfaces of one board facing each other. The surface, or the board, is made of 60×56 tiles on a grid. Since it would be damn near impossible to design a game with 3300+ tiles in one screen while programming something that actually can be played, the player’s view consists of 9×5 tiles instead. Subsequently, this means that you can scroll the board in all four directions. The same of course goes for the opponent. The thing with Flashpoint is that you are shooting up shit on the opponent’s grid while trying to avoid getting your shit shot up. But instead of scrolling the enemy’s board view to find bit to blast to pieces, you have to use a somewhat reversed strategy, i.e., pay attention to when targets appear in your line of fire.

The fact that the board is viewed from two separate 45-degree angles isn’t just a graphical gimmick or because it looks cool. First of all, you have to place out your forces on the grid. The tokens on the right sides of the boards show how many units you have in store. The game begins with 80 pieces. (So there is one token marked “64” and two marked “8” on screen. (64+8+8.) The stacks change like in a game of Roulette, e.g., when one unit is taken from the “64”-token, it breaks up into one token marked “32”, three marked “8”, and seven marked “1”.) To pick up a unit, you hold the Fire-button pressed and push down on the Joystick. (The arrows pointing at the center tile turn yellow.) Then you move around the field and place the unit wherever you want. (By holding Fire and pushing down again.) Your forces are the green tiles on the board and the opponent’s forces are the red ones. The same goes for the opponent’s board, i.e., your forces are also green on the opposite side. So you can always see where your enemy has placed his / her forces since the board is the same. (It’s only the views that change constantly.) When all forces are in place, the battle begins.

And this is where the main mechanic of Flashpoint comes into play: That extra semi-dimension where the straight and diagonal lines between the boards equal different distances depending on where the two players’ points of view are placed. For example: Let’s say you move the view into the lower left corner of the board. We’re going to call these co-ordinates 1,1 according to the x- and y-axes. (Whereas the top left corner would be 60,1, the top right corner 60,56, and the lower right corner 1,56. Pretty basic high school math.) Here, at 1,1, you place a unit. It simultaneously appears on the opponent’s board, i.e., your unit can now be seen at co-ordinates 60,1. (Relative to the screen.) Which simply means that you play against an upside down mirror image of your view of the board.

The objective is to take out the enemy units one by one until you get 2.000 points. This blasting business can be done with the the units or the laser-cannons. You can never fire from the center tile. And you can’t fire while moving units. To take out an enemy unit, you align a green unit and a red one and press Fire. These can be aligned both horizontally and vertically. (Once again, relative to the screen.) As mentioned, the grid view is 9×5 tiles. So if a red unit is on the, e.g., third tile from the top and the second tile from the left, you can blast it if you have a green unit on the third tile from the bottom and the second tile from the left. Because “mirror images”. And you are only able to fire when there is a target in your line of fire.

Placed on the board from the beginning are also five different laser-cannons. (They can be moved around by both sides. And they keep switching places and teleporting around the board randomly.) There is one cannon that fires up at the tile that’s in line – Let’s use co-ordinates again for clarity where 1,1 is the lower left corner of the grid view, 9,1 is the lower left corner, 1,5 is the top left corner, and 9,5 is the top right one. So if you have this upwards firing cannon in view at 4,4 and the opponent has a unit at 4,4, it would be disintegrated.

Another cannon fires four tiles left, i.e., four tiles left of the opponent’s corresponding tile. (From the “camera’s” point of view. So your unit at 5,4 would destroy one at opponent’s co-ordinates 1,4.) The third one fires four tiles right. (Again, a unit at 5,4 would impact co-ordinates 9,4.) The fourth type of laser fires from either of the two corner tiles that are closest to the “camera”, and the laser impacts the opposite side’s corner tile. (For example, your unit at 9,1 would destroy the opponent’s unit placed at 9,1.) The fifth cannon fires from either of the two corner tiles furthest away from the camera. (So reversed, in other words.) Likewise, the blast from these hit the corner tiles closest to the camera, i.e., a unit at 9,5 would strike one at 9,5 on the opponent’s side.) These units can furthermore be placed in formations for more effective destruction.

To see where you risk getting blasted, you have to constantly glance at the opponent’s board perspective. The vertical edges of the grid are lined with cyan-colored tiles and the horizontal ones are solid blue. Additionally, there are cyan-colored tiles evenly placed as markers along the edges. (Plus double yellow ones that point out the middle of the field.) All the tiles are collectively useful as a visual guide since you have no other way to compare in which direction the board scrolls or if it scrolls. (Since it jump-scrolls one tile at a time.)

Flashpoint does get some serious time to get used to, but there is a sweaty and hectic game underneath the odd double vision. And there’s the challenge factor that compares to any tactical action game that relies on eye-hand coordination. And if you can find another player that becomes as skilled as you, you might end up in legendarily severe showdowns.

But the game’s fate still boggles the mind, though. If nothing else, Ocean proved that getting a bit too comfortable with any situation is the enemy of creativity – Especially when certain games could sell with another nice little ad… We’ll harp a bit more on the same string… Right now, as a matter of fact… — Release: Fall (November) 1989 (Developed in summer (?) 1987.) · Credits: Stuart James Fotheringham, Fred Gray · ZX Spectrum 48K (Cassette)

Note: Sinclair User also released Flashpoint on a cover tape in June 1990. (Issue #100.) The tape was called “Double Hits 1”, and it also featured Terra Cresta. Five of these “Double Hits” were released during the following months. Tape 4 featured Mutants, and Tape 5 had none other than Gift From The Gods. So they knew what was good.

Starace (Zzap! 64 / Ocean) – That Zzap! 64 had a cover tape with various goodies on it was nothing unusual at this point. (One example of a solid gem was “Zzap Music” in June 1989 with five excellent Martin Walker tunes.) But with issue #65, there was something special special – Two full games on the tape: Romik Software’s 1983 classic Dicky’s Diamonds, and Starace by– Holy shit?! Denton Designs’ Starace…?! While it basically was almost too good to be true to get a full C64-game this time around from such legendary game developers, practically for free, it immediately begged the question: Why did it happen? And this of course lead to the more burning question: Why the hell was Chase H.Q. being sold at full price when Starace was “dispatched” to a cover tape…?

Starace was another game that was developed back in 1987 (That’s three years before Zzap! 64 bought it from the Dentons.) and it was probably scheduled to be published by Ocean around the time Mutants and Madballs were released… (Maybe even between those two games.) But then… Ocean downright refused to do it – Claiming that the game would be hard to sell…

So let us get this straight once and for all, god damn it: The same publisher that decided to release and market Highlander, Cobra, Knight Rider, and Top Gun thought that Starace wouldn’t sell…? That it was a “too slow” of a game… Highlander, Cobra, and Top Gun sure as hell had fantastic soundtracks, but as video games with genuine and long lasting entertainment value, there wasn’t honestly that much that came with them… (Everybody just remembers the soundtracks.) Especially not to justify the price that they initially cost. (And Top Gun wasn’t exactly a “lightning fast” gaming experience either.)

The loading screen to Starace has a bit of the same vibe as the one to Mutants. Both have something distinctly astral over them with various organic-looking shapes in the foreground. In the case of the Mutants loading screen, it’s those hostile organisms hidden in plain sight. With Starace’s image, it’s like a continuation of the same theme with the red / magenta-colored soft shapes on the left. But the image features a triangular shape dominating the image. (And something that’s probably an extraterrestrial station in the background.) This basic geometric shape is also what also dominates the game. (Attempts at explaining follow.)

But what is “Starace”…? In the future, after bright minds discovered that it was possible to travel vast distances in space in a relatively short time by using the near-infinite power of stars, they constructed these tunnels for that very purpose. But the minds of a far more competitive nature, with the undying need to speed, figured out that these tunnels could double for some very exciting competitions. And so, the concept of Staracing, racing with the help of stars, was conceived. These races are fast but of non lethal character, thanks to the giant Toblerone-tube shaped force-fields that form the winding tunnels.

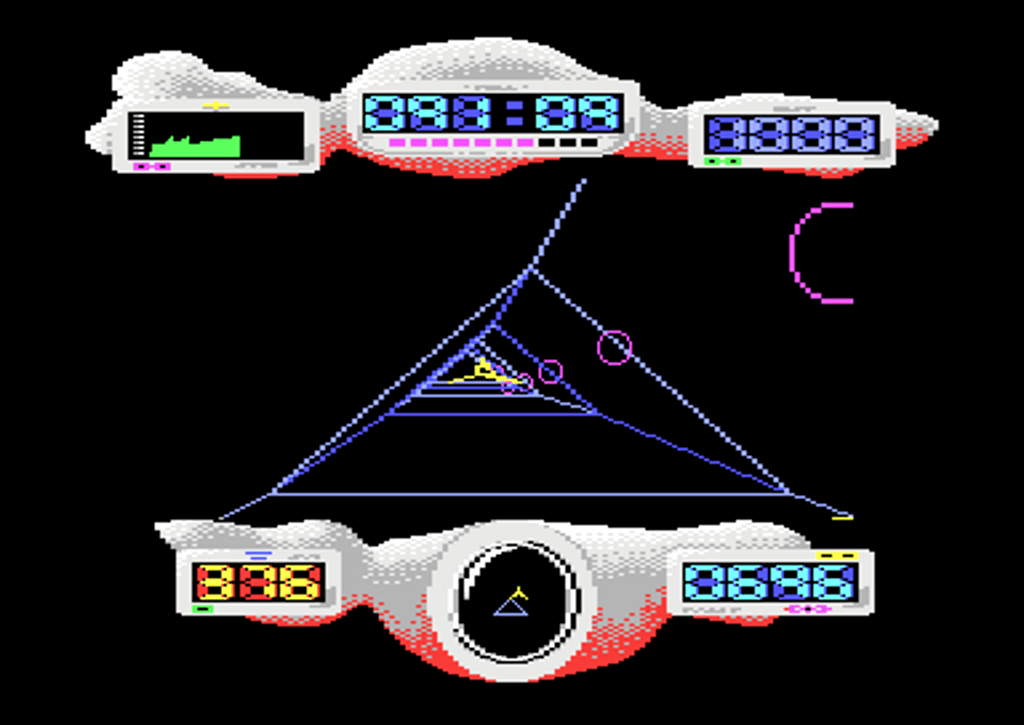

After loading, the title screen opens up – Two asymmetric, blue-tinted shapes at the top and the bottom of an otherwise black screen displaying “DENTON DESIGNS PRESENTS STARACE”. The lower (smaller) blue shape is a menu that’s so far ahead of it’s time that it still looks modern, futuristic, AND 80s Retro at the same time. And it mimics the buttons for a stereo. You control this interface with a severed hand while an excellent Fred Gray-track plays. The menu buttons are marked: PLAY, TRAK, HI, and DATA. There is also a volume slider (From MIN to MAX.), and MUSIC. (ON / OFF.)

Changing the volume and turning the music on or off are self explanatory, just like any button that says: PLAY. But before you get to race, you have to select a track including its difficulty level. This is done by clicking the DATA button. This brings up a screen with the track selection (There are fourteen more or less Satanically difficult ones.) including the track name, set difficulty level, and control type. A short comment about the current track is also displayed. The difficulty levels are: Novice, Amateur, Professional, and Expert. And the control types are: Demonstration Mode, Manual, Computer Alignment, and Computer Assisted. The Demonstration Mode simply shows the track played by the CPU, Computer Alignment auto-pilots your ship back into the tunnel if (when) you end up outside it, Computer Assisted helps you stay centered inside the tunnel, and Manual control… Well, that’s for the true Pro Staracers. Press the UP and DOWN buttons to flip between the tracks, and then, you can either check the track from different angles, see the Hi-scores, or race.

Clicking the TRAK button shows nothing but the layout of the track as a yellow vector graphics-rendered continuous line in the middle of the screen. Every time you click on TRAK, the layout rotates on the z-axis a number of degrees, revealing any elevation, the sharpness of turns, and such. (There are seven different views including the view from the side.) The HI button takes you to the menu with all the “Starace Champions” – Each table includes the names of five racers plus their positions and scores for each track. These lists can also be flipped through with the UP and DOWN arrows in the top right corner. (And logically, there are 14 “Top 5”-lists.) But how do you prove your glorious achievements after the game has been turned off? Easy – There are options for saving and loading in this menu. (The icons look like floppy disks and C64s even if the game was never released on disk.)

And then, it’s time to click PLAY. The menu slides off screen and your ship’s control panels (Top and bottom.) slides in. The left part of the top panel displays a graph that functions as live race stats – The display gradually fills up with green as your current position and distance constantly is registered with regular short intervals during the race. The x-axis represents the distance and the y-axis represents your position. In other words: The more green, the better. In the center of the top panel, right of the graph, you see how much of the track is left (As a numeric value.) including your position. Below the “distance / position”-display is your speedometer. Velocity is represented between 1-10 as magenta colored LEDs. The four-digit number in the top right corner is the current tracks best time. The bottom panel shows your velocity (Also as a numeric value.), a radar that shows where the tunnel is compared to your vessel, and your time. (One unit of time seems to equal a quarter of a real second.)

Before the race starts, the word “STARACE” zooms in and the letters transform into the triangular tunnel that you’ll be staring down at all times. A press of the Fire-button counts down from five to zero, and the race is on… The race itself is all about passing as many of the other opponents as possible, stay within the boundaries of the tunnel, and get to the end as fast as you can. Flying outside the boundaries decreases your velocity, and the faster you fly, the harder it is to turn. Colliding with other ships makes you spin out of control, and smacking into the magenta colored floating bollards not only cracks your windshield, but fucks up your ship. But no worries – It’s in racing condition again as soon as the computer override has placed it on track again. After a race, you see you final position and time.

Starace is solely built on vector graphics, which might not always be a good idea to do on a C64-game relying on speed. But thanks to the minimalistic appearance, the game is fully playable with fully acceptable frame-rates. The tunnel is rendered as blue lines, the bollards as magenta-colored circles, and the opponents appear as yellow wire-frame ships. Starace could almost be seen as a very early predecessor to WipeOut… Yeah, I know… It’s all about the velocity in the end – This isn’t an ultra-fast game and you won’t be flying down the narrow tunnels in realistically represented illusions at breakneck speeds, but there is still a good sense of motion. And skill is needed to win. Which you’ll gain if you race over and over again and learn the controls. The in-game music is another one of Fred Gray’s memorable tunes. Plus the sound effects with multiple channels generating the drone of the ship’s engine is quite hypnotic and strangely soothing.

If you love futuristic racing games with both style and substance, but not necessarily the smoothest gameplay you have ever experienced, Starace is worth a couple of rides. If there is one thing that the game is, it’s overlooked and underrated. But once again, we return to the notion that the whole circus that was going on beyond Denton Designs’ control was another sign that Ocean was losing the plot. Something quite disadvantageous happened from an artistic point of view. Some of the movie tie-ins sold a little too well, I think. What really could have saved the publisher in the long run was simply sticking to their guns – Continuing to build up the legacy of amazing software. And Ocean could have been around to this day.

I think Steve Cain once said it best: “The software industry could be generating brilliant characters and licensing them out to films and TV, but look what happens. We end up having to write a game about some crappy American TV series. It’s the wrong way round.” And look what happened. Those predictions and prophecies aren’t without their sick sense of replacement humor sometimes. — Release: Fall (September) 1990 · Credits: Dave Colclough, Stuart James Fotheringham, Fred Gray · Commodore 64 (Cassette)

(To be concluded…)