Art For The Machines: Part III – Everything Changes (Everything)

1986-1987

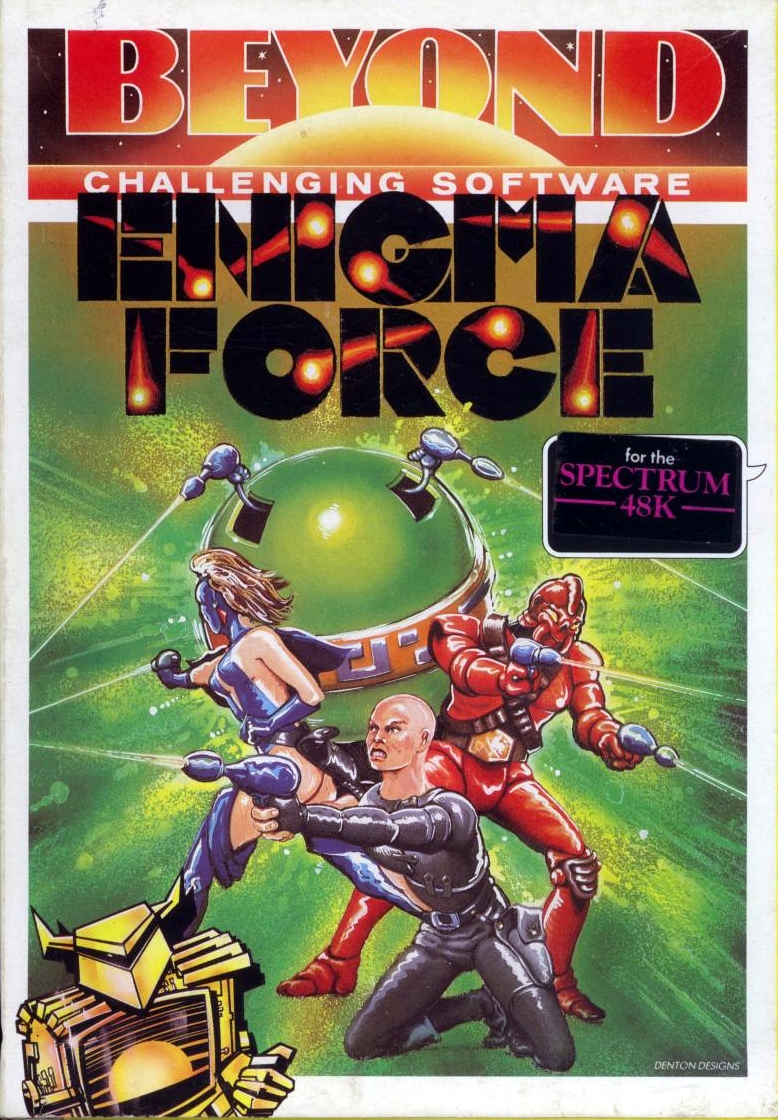

Enigma Force (Beyond) – Shadowfire 2… Phew… Just imagine the pressure – How the devil do you even follow up with ideas to one of the most original games in video game history? Expand on the first one? Or take the easy way out? (By changing a couple of things around and in the process produce something sub par, hoping that the fans will buy it no matter what?) No. That would be an act of burning bridges and sinking to uncharted levels where you discover one day, sooner not later, that you have turned into a predecessor to modern day Electronic Arts… Then imagine the fans’ expectations growing as the release date draws nearer and nearer… I have no idea how angst-ridden or troublesome the production cycle for Enigma Force was, but at least Beyond must have had some strategy around it… Reverse engineering the Shadowfire Tuner and outsourcing everything else would have been so easy and so… Well, like a shitty video game producer would have done it in order to get the game out sooner… But was there ever any doubt that Denton Designs wouldn’t deliver? Of course there wasn’t. And with one single game, they showed how sequels are supposed to be done. So why didn’t “everybody” take notes?

“SHOOT-em-UP or STRATEGY – You choose” and “Amazing interactive animation” proclaimed the ads. “We’ve taken the icons out of Shadowfire; Developed some incredible animation techniques; And composed a powerful music score… The result?… …An adventure in which you see, hear and experience the action!” – More absolute truths courtesy of Beyond Software, in other words…

“Welcome to Enigma Force”, reads the computer screen on the very first screen in the game. “Computer security alert. Unknown user attempting entry.” … “Security code accepted.” … “Disengage hyper drive.” … “Hyperdrive disengaged.” … “Unlock Zoff’s freeze hold.” … Hey, wait a minute…?! “Warning. Zoff is now free.” Son of a bitch?! “Scan database for nearest Republican force.” … “Planet Xylon.” … “Set course for Xylon.” … “Escape shuttle entry.” … “Shuttle launched.” … “Zoff has escaped.” … “Crash landing imminent!” Oh– … “Crash landing successful.” … “Crew freeze chambers open.” … “Crew awake. Their mission… Neutralize Zoff!” (This introductory text reads quite differently on the Spectrum-version, but it too ends with the Enigma Team crashing on planet Xylon… Time to paint it red…!)

So after the successful capture of General Malthadius Zoff in Shadowfire, you are on your way back to bring the arch bastard to trial before the Emperor. While you’re relaxing in cryo-sleep, your ship is flying towards its destination… But like the slightly predictable sociopath that Zoff is, he breaks free with the help of his mental powers and fucks up the ship’s hyper drive. This in turn forces the craft to crash while Zoff himself escapes in an escape shuttle. After the hard landing, the ultimate bad-asses Syylk, Sevrina Maris, Maul, Zark Montor, and you dust yourselves off and prepare for another mission. If the Enigma Team has reported that they will bring Zoff to justice, then the Enigma Team will bring Zoff to justice…

There is an ulterior reason why Zoff chose Xylon of all planets to crash on. It just so happens that there are Reptiloid forces in war with the local Insectoids. The Reptiloids are Zoff’s boyos, but Xylon just so happens to be Syylk’s home planet. So there is extremely bad blood between the two “oids” from the beginning. What’s worse is that Xylon is on the brink of total destruction. So now, the Enigma Force are in really deep shit. Their mission is to: 1) Find the leader of Syylk’s allies and recruit him. 2) Prevent Zoff from escaping Xylon with the only functioning space craft – Before the Destructor Tugs tear the planet to pieces. 3) GTFO.

But… Where the hell are Torik and Manto…?! Their absence could be explained with both of them getting killed in the crash at the beginning… But in what definitely could be a video game first, the game could also replace an original character with the player. (Manto in this case.) As far as you know, you are the Team Leader, and that might very well “be” Manto in spirit. Either way, it was a fantastic choice story-wise to pick up where the original left since the “5 years later”-exposition could have gotten old pretty much immediately. Plus the now familiar characters is such a lovely bunch.

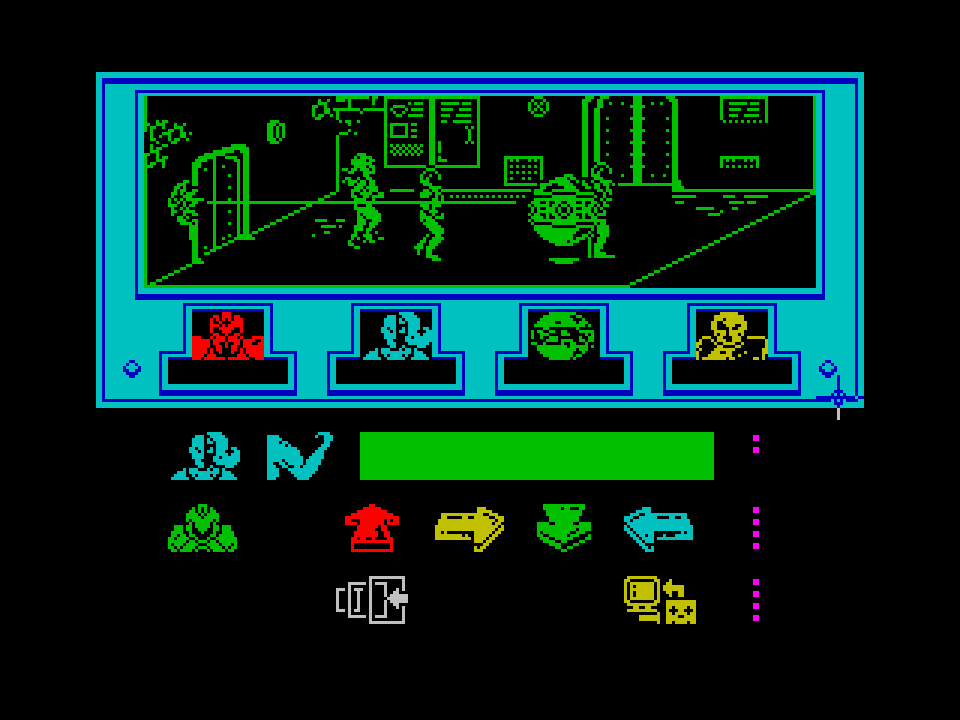

Apart from the game’s real-time aspect, you will immediately notice a big difference when comparing Enigma Force to Shadowfire. The screen is now divided into three sections: 1) The upper one is the place where it’s all happening. (Locations and animations. The characters walk from screen to screen and the battles are fully animated.) 2) The middle part has pictures of the four characters including their power-bars and command-windows. 3) The lower section is a sideways scrolling strip with multiple icons. This strip is further divided into five sections. These should look familiar from Shadowfire as there are the character-, movement-, battle-, and object-icons, plus icons for Pick Up, Drop, Activate, and Load Weapon. (The Pick Up- and Drop commands are illustrated as briefcases that a hands picks up and drops respectively. The Activate command shows a finger pushing a button. But the “Load Weapon”-icon is pretty cryptic. It looks like the top section of an ammo clip with an arrow pointing at a gun.) Note that the Agility- and Stamina-bars from Shadowfire are absent in Enigma Force. The characters “only” have an individual Strength-bar. (And in this game it’s all that’s needed.)

As for the aforementioned “command-window”, you can “pre-program” each character with up to eight directions and commands. (Five on the Spectrum version.) The sequence is dynamically shown as tiny icons in the window on the right side of the respective character’s portrait. For example, if you click the “Up”-icon three times, three small “Up”-icons appear in the command-window, and they disappear one by one as they are executed. In this case, the character would move up three screens / times. If you regret a command-sequence, you can click the “Oops”-icon to cancel one, several, or all of the inputs.

Enigma Force is sixty-three flip-screens big and plays out in isometric view. You select one character at a time, move from screen to screen, find / use objects, and explore the maze-like Xylon underground. Very often, you end up in battle, and that’s when you should have fully loaded weapons and enough ammo. Ammo can be found all around the map. And the icons to use when you encounter enemies here are either: “HOUND TO DEATH!” or “DEFEND & HOLD!”. (The symbol for the former shows an arrow pointing right from a square, and the latter has a double-ended one that points both left and right.) The “neutral” command is to retreat… But it’s always a rush chasing a defenseless Reptiloid into a room and murdering the Mofo after some initial instigating from their side. This is what the “HOUND TO DEATH!”-option is for. “DEFEND & HOLD!” is when you wish to “engage all the enemies in one room”. The characters in Enigma Force live a life of their own. It’s not uncommon that they disobey your orders if they’re either insane or just plain stupid. (You can’t send a character with empty guns into a room packed with Reptiloid a-holes without the character panicking, for example.) But if you wish to control a character directly, there is the “Mindprobe”-icon. (Which looks like a brain with three arrows pointing at it.) The “Game Status”-icons throws up a screen that displays the characters’ health, Insectoid and Reptiloid casualties, and mission status.

The focus has shifted quite a bit in Enigma Force. As it’s more action oriented instead of strategic, it also requires a different way of playing it. It’s not impossible to imagine that some people liked one of these games better than the other and that Enigma Force clicked with the die-hard fans who “got it” and found it to be the natural evolution to Shadowfire. This was a time when the demand was increasing for more exciting visuals and action. (While the board-game layouts and graphics with limited animation were left for the full-on strategy games.) But this is not to say that the strategic and tactical aspects are missing in Enigma Force. You really need to have some brain capacity going forward if you don’t want to see the Enigma Team slaughtered within the first few minutes / screens. (And that usually does happen the first time(s) one plays the game without reading the manual.)

In my opinion, Enigma Force is The perfect sequel – It immediately feels fresh and interesting. It has several new features and a well-designed system that takes the best bits from the original and improves / adjusts them for a completely new style of gameplay. The use of icons is slightly different, but not unrecognizable, which should make the interface easier for a veteran Shadowfire-player to get into. The visuals are are lovely, of course – Colorful, characteristic, and cute (Subjective appreciation.) on the C64 and more detailed and realistic but monochromatic on the Spectrum. (The background graphics in this version are color-coded after each character – For example, Maul’s character portrait is green, so when you control Maul, everything is green. Simple.) As with the other Denton-developed games, you should play the game on both platforms to get the best of both worlds. Fred Gray’s theme (2.06) is naturally superior on the C64, and it’s a bit of classic music with a wonderful and uplifting melody and both intricate and dramatic progressions. (The Spectrum variant is shorter (1.40) as it plays slightly faster. It’s way more primitive if you will, but a killer tune is a killer tune regardless of which instruments it’s performed with.)

If Shadowfire got the perfect box cover art, then Enigma Force shouldn’t get anything lesser, right? And it didn’t. Since the game’s focus is on action and Zark is the action man of the team, he is fronting the quartet this time. And all four are blasting non-stop at something off screen. It’s a fantastic piece of video game box art, and it displays both intense drama and some sensuality – Just like the original cover for Shadowfire. The loading screen is also one for the galleries. It shows General Zoff sitting in front of a huge computer terminal, tirelessly planning mayhem and destruction, and how to take over the Empire. (That huge “Enigma Force”-logo probably makes his blood boil, though.)

Last but not least, and sadly, there was no Enigma Force Tuner released later on, and even more sad is it that the franchise ended with this game. (But never say never? Except in very rare cases.) There was of course potential for much more – Even if subsequent games couldn’t probably have broken as much new ground in the now explosively expanding video game industry. And this is where Denton Designs, as a company, started to move in a different direction. But the Enigma Team lives on in the hearts of the fans. And it’s only normal to wish for a sequel to something so utterly great as these two gems. — Release: Winter / Early (January) 1986 · Credits: (C64) Simon Butler, Steven Cain, Dave Colclough, Karen Davies, Fred Gray / (ZX) Simon Butler, Steven Cain, Karen Davies, John Heap · Commodore 64 (Cassette / Disk) / ZX Spectrum 48K (Cassette)

Note: The Amstrad CPC did neither get the Shadowfire Tuner nor the sequel. That’s harsh. And a good reason to get a C64. 😉

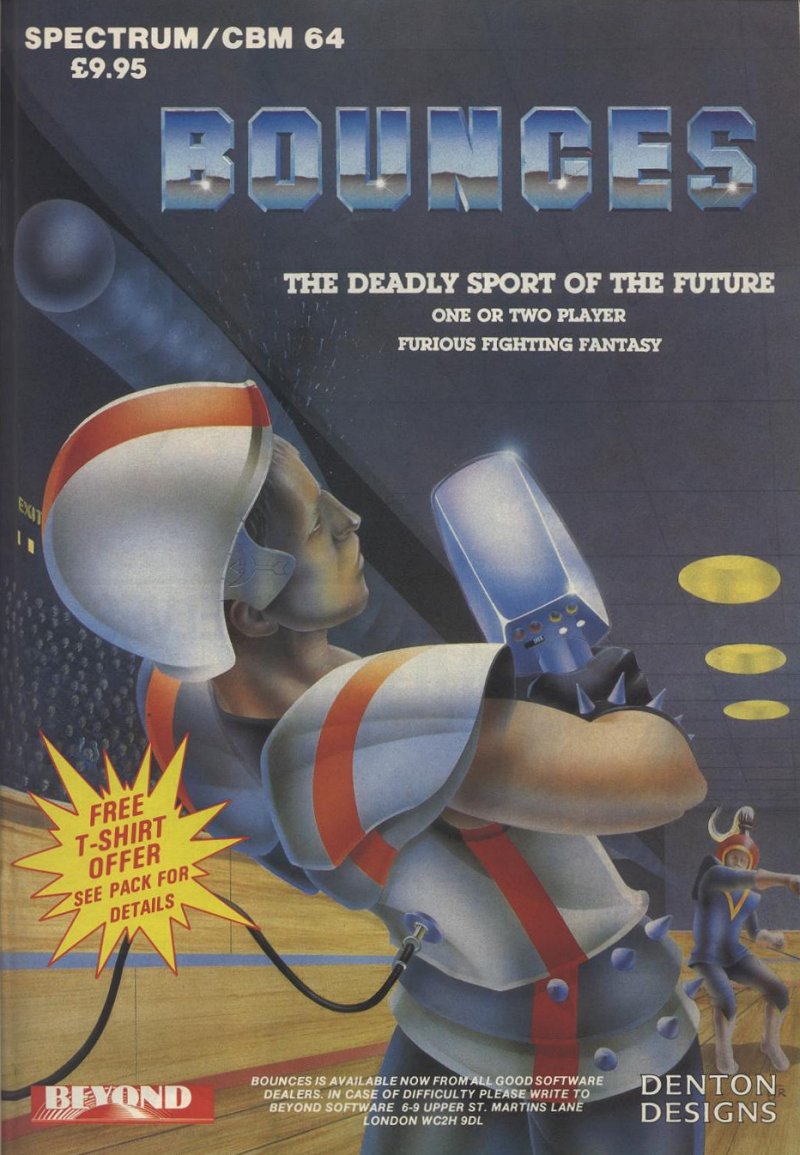

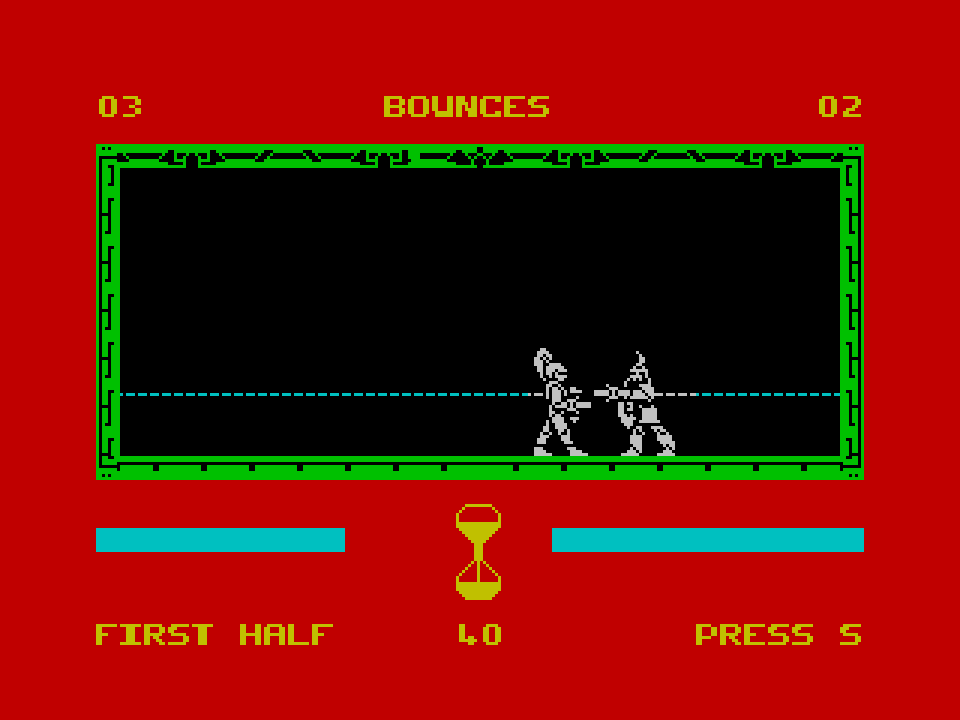

Bounces (Beyond / Monolith) – Bounces was this slightly mysterious “future sports”-orientated game that was announced for Christmas 1985 already. But as far as various archived magazines and adverts can tell you, the game wasn’t out, or at least reviewed, until spring / early summer of 1986. (Was these some of the early signs that certain crucial things weren’t quite O.K. over at the Dentons?) But the fact that the game was developed by a certain team game generated interest by default – Especially with that ad depicting a Rollerball-esque moment in a cold-looking arena where the central character is violently hit by a ball. The following reviews for this combination between a player vs. player fighting- and ball game were mixed. (Although some were very positive.) But in the game itself, there was a clear absence of options – The most notable one, being able to choose between eight different character types, was nowhere to be found in the released product. (This was mentioned in the July 1985 issue (#40) of Sinclair User.) In an interview, Graham Everett added: “The Spectrum version of Bounces was a complete load of rubbish – The difference was about three months of playtesting.” So apparently, something did happen on the way. Something that eventually turned into the straw that broke the camel’s back.

The idea for this untraditional action-based game was reportedly born thanks to Frankie Goes To Hollywood. (As in the game.) It takes places in the future where there is no war, politics, or unemployment. (Sounds good enough, already!) Conflicts are solved through Bounces! – Two opposing sides from any tense fractions enter an arena packed with a blood-thirsty audience. Each side is represented by one combatant. And each combatant has Fric-Toe boots, a body armor, a helmet, and a Bounces! ball-snatcher. Plus an elastic cord attached to the waist.

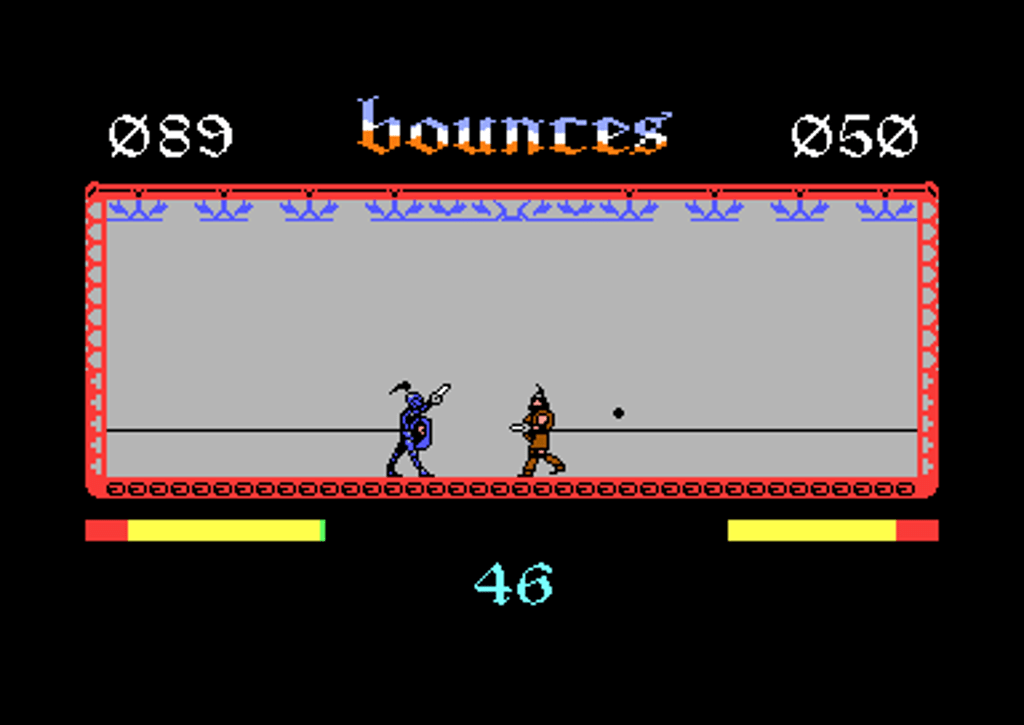

Bounces puts Eric The Red from the Vikings (Sponsored by Viking-Synthi-Corp.) against Sir Ashley Trueblood from the Knights (of Knight-Techni-Corp) against each other. (This is where the choice of characters dramatically would have increased the value of the game.) In matches lasting for 2 x 90 seconds, the players have to score as many points as possible. This is done with the help of a ball that bounces around the arena through the magic of perpetual motion.

The game is viewed from the side with the fighters facing each other. The ceiling of the arena has goal slots. (Three on each side.) To score, the ball has to enter via one of the slots. The goals award a different number of points depending on how far away from you they are in the moment of penetration. The opponent gets the points if you shoot the ball into your own slot. The ball can be caught with the ball-snatcher. And you can aim where you want to launch it. The ball has power enough to knock a player off his feet, but the players can also use the ball-snatchers as weapons against each other. The elastic cord makes the whole deal a bit trickier. The farther away you are from your side of the wall, the stronger the pull of the cord is. (You’re just lucky that it can’t snap.) You can make short jumps, and this causes you to get pulled backwards through the air. (Jump when you’re far away from the wall, and the force inevitably pulls your ass to the ground.) But what the audience really wants to see (As they are starved for violent entertainment elsewhere.) is the two armored players knocking each other out in fast and short bouts. Slug the opponent in the eye with the ball-snatcher, and the cord usually does the rest of the job. Absolutely humiliating. After one half, the combatants switch sides.

The players have an on-screen stamina-bar that gets depleted when you do just about anything else than stand still. (And that’s when it regenerates.) The Spectrum-version has an hour glass above the timer that counts down each half of the match while the C64-version sports a stylish font for the stats. (Score and time.) The game may not have anything in the shape of imaginative and varied backgrounds, but the visual focal point is on the character definition and animations. The Hi-res Sprites on the C64 are done with overlays so they have both the details and multiple colors. (Five for each character.) On the Spectrum, the players are monochromatic, but the lovely details are there. Not to mention the animations! And this calls for another quote from Graham Everett: “Look at Bounces – That has eight frames of animation when the player falls over. Nobody noticed that – It was dead smooth cartoon animation and nobody noticed it. Nobody cared about the flicker-free animation. Things like that are so annoying.” So very true. And Bounces just plays very well. Once you master the controls, you notice what a lovely game there is “hidden” beneath the minimalistic first impression.

As mentioned, the gameplay options aren’t that many, but they are sufficient. (Given the circumstances.) You can select which of the two characters to play as, there are two skill-levels (Beginner and Expert.), and you can play against the computer or a living being who knows how to handle a Joystick.

The programming and graphics credits for the C64-version are not explicitly mentioned “anywhere”, but it’s a qualified guess that Karen Davies did the graphics (Including another iconic loading screen with the two stars of the game.) and Graham P. Everett did the programming. (With or without David Colclough? Or was it the other way round?) This is really like trying to piece together at least three different jigsaws where some pieces missing. Bounces on the C64 has another one of Fred Gray’s hits on the title screen. It’s another short and lovely piece, lasting a mere 104 seconds. But it’s a thoroughly pleasant 104 seconds. (The music does have a strong Shadowfire-vibe, but there isn’t one bit of melody that is the same. And it links these games together in an even better way.)

So if you are on the lookout for a game that depicts “The deadly sport of the future” that equals “Furious fighting fantasy”, you should definitely check out Bounces. But you might want to keep expectations at a low level if you dream of a game that suits the description with epic tournaments, multiple arenas, a sense of action and motion – With a fanatic crowd cheering on during an escalating blood-thirst… Because there is none of that present here. Instead, it’s concentrated on the battle. Bounces has its own thing going on, and the best part of all – It doesn’t remind of any other sports games. — Release: Spring (April) 1986 · Credits: (C64) “Denton Designs”, Fred Gray / (ZX) Simon Butler, Steven Cain, Graham P. Everett · Commodore 64 (Cassette) / ZX Spectrum 48K (Cassette)

Note: Co-publisher Monolith isn’t to be confused with Monolith Productions known for games like Blood. (1997) Monolith and Nexus, as in Beyond’s sub-labels, were founded with the purpose of differentiating between the company’s action, adventure, and strategy games.

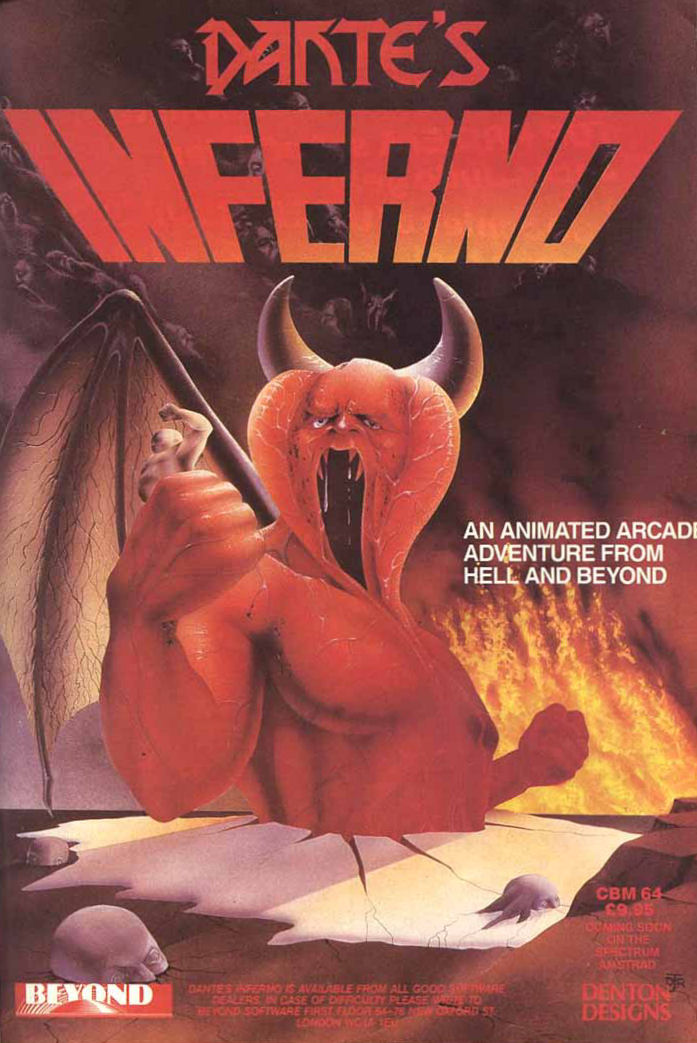

Dante’s Inferno (Beyond) – It was probably around this time (And obviously before Dante’s Inferno was in development.) when the old Denton Designs team split up – Steven Cain, Karen Davies, and John Gibson left for various reasons, and new blood joined. (In an interview in CRASH magazine, January 1987, money was mentioned as one of these reasons. And the fact that the others wanted to go freelance… And make more money…) The “New Dentons” were: Dave Colclough, Stuart James Fotheringham, Andy Heap, John Heap, Ally Noble, and Colin Parrott. (The story behind this split was also featured in the Zzap! 64 Christmas Special 1986/87, and it quite naturally explains the months long gap between releases. The team simply had to adapt to the new situation.) The big question was of course how this would affect the games going forward. With at least a significant part of the original team still being intact, there would at least be no worries as far as overall entertainment- and audiovisual values were concerned… But would we ever see something of Frankie’s och Shadowfire’s caliber? Only time, and 1987 just around the corner, would tell.

Anyone who is familiar with Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy should know about the Nine Circles Of Hell. Just like Gustave Doré’s paintings would tell, they are not at all nice places – Each new discovered one notably worse than the last. And the journey depicted in the book is this spiritual pilgrimage through seething self-deceit and looming threats of eternal suffering. So that is partially what’s on the agenda for the protagonist in the video game version as well – With the only real problem being that in the 14th century, Alighieri couldn’t play this exact video game and make things at least slightly easier for himself. But it’s a good theme to base a video game around, and a thankful one to insert into the wide genre of arcade adventures. And both the cover art and the loading screen for Dante’s Inferno is intriguing to say the least. (That’s another thing that put Denton’s games above the rest – The loading screens… Except for the one for The Transformers, then…)

“In the middle of the journey of our life I came to myself within a dark wood where the straight way was lost. Ah, how hard a thing it is to tell of that wood, savage harsh and dense, the thought of which renews my fear! So bitter is it that death is hardly more. But to give account if the good which I found there I will tell of the other things I noted there.” – Is this an observation of the video game industry moving into that wood, savage harsh and dense, or something entirely else? Think about it.

So which bits, pieces, and good stuff from the ~100.000 word poem survived the transition to the mighty 8-bits? The journey. Squeezed into nine shorter levels. With some recognizable characters. This is basically a four-way scrolling arcade adventure with some environmental puzzles that fluctuate between dead-easy to somewhat tricky in difficulty. With sequences of the “Avoid it”-subgenre. Dante’s trip starts in the Limbo Circle, which could be anywhere in the peaceful countryside. But this is where a scrolling note tells you to “Abandon every hope”. After picking up two items that fall under the category “Better to have one when you don’t need one rather than not having one when you need one”, Dante can start taking his business elsewhere – Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. And once he saunters into a tunnel leading underground he will need some coin. Because the subterranean ferryman known as Charon won’t let him ride down the Styx without some real currency. Missing the ride gives Dante two choices – To either get stung to death by a legion of hornets, or jump in the river and drown. It’s merciless down below.

And then, you have the remaining Circles – Lust, Gluttony, Greed, Sloth, Wrath, Pride, Envy, and Treachery. (No Pleasuredome! Unless your pleasure is suffering, fire, hideous creatures with whips, and such.) There are also demons, zombies, hell hounds, and Satan himself. (And a dragon. Plus Medusa. It just isn’t a swinging party in the Purgatory without certain elements present.)

Dante has just about one week to complete his infernal journey, face Satan, and get out as a better human being. (Then back home for some chilling, hard drinking, getting salty over shit, before hitting the whorehouses with a generous supply of blow. And feeling good about it, of course…!) But since the game can be completed in mere minutes, a day passes in a couple of moments. But before you ever get to those levels of playing and regretting stuff so that you can do it all over again, there is some heavy trial and error going on. You need to get the exact right items, navigate maze-like sections, and stay away from more or less everything.

Dante’s Inferno was advertised for the ZX Spectrum, but it was never released (Quite possibly due to the team splitting up prior.), so it indirectly ended up being a C64 exclusive. As with many of the “New Dentons”-games, the credits are partially unknown and officially undisclosed. But this game was, probably, programmed by Dave Colclough. (It’s not a totally uneducated guess.) And the graphics were, also probably, done by Stuart Fotheringham and Ally Noble. (Seeing she was the graphics artist and all.) Fred Gray’s soundtrack is as close to classic music as we’ll ever get on the SID-chip. There is a couple of short “Johann Sebastian Bach”-pieces crammed into 3 (Three!) KB. (Plus some jingles.) It’s one fine OST that fits the game and theme, and that’s really all you can ask for.

Granted, with Dante’s Inferno being a single-load game, the variation in the visuals can’t be “unlimited”, but what’s there is pretty damn atmospheric. Rocky labyrinths, lava rivers, and dead places – This 8-bit hell looks relatively good. And if anyone could have crammed as much as possible into one game, it was the studio that had developed Frankie. (The company magic was clearly alive.)

When compared to the already classic games by the Dentons, it has to be said that Dante’s Inferno is more of a middle of the road type of game that is veering towards the really good ones. There is nothing wrong with it – It’s quite well done, plays well, is aesthetically pleasing, is based around an interesting theme, and has suitable music. And it’s light years better than The Transformers… But it’s not in the same league as Frankie, Shadowfire, or Enigma Force. (And how in Inferno could it have been?) — Release: Winter / Late (December) 1986 · Credits: Stuart James Fotheringham, Fred Gray · Commodore 64 (Cassette)

Trivia: This game is of course totally unrelated to the 2010 game by the same name that was developed by Visceral Games.

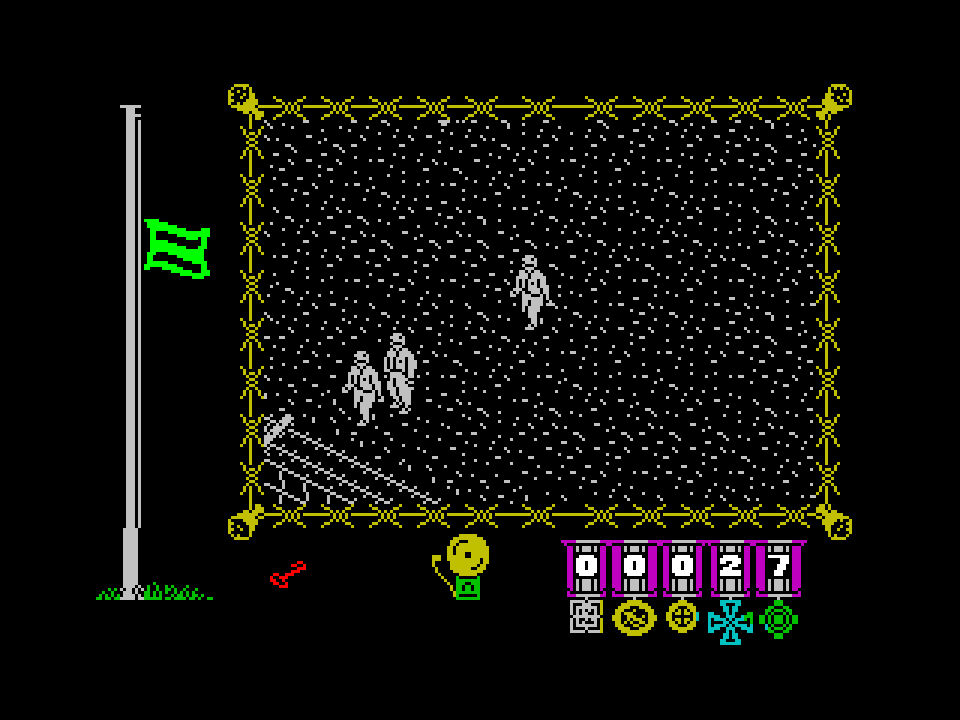

The Great Escape (Ocean) – It’s 1942 and World War II rages on – Who knows for how long… One day, you are captured by the Nazis and the next thing you know, and right when the game has loaded, you find yourself in a barrack outside a German castle. The castle is surrounded by barbed wire fences and a couple of guard towers as the whole place has been turned into a P.O.W. camp. You, along with a bunch of your fellow countrymen, have been placed in a bunch of the aforementioned barracks. The uncertainty regarding the end of the war and existence in the camp isn’t the least entertaining, so you are immediately and seriously planning to get the hell out of there – Preferably as soon as possible. The fact that the three sides of the castle faces the North Sea only leaves the south side as a possible escape route. And that’s a major problem.

Each day in the camp is more or less exactly the same. (Waiting to find out what’s in the new Red Cross parcel arriving in the day – That’s about as exciting as it gets… Unless you figure out something else to do…) It starts with a head count on the yard. (And you’d better show up.) Then breakfast. (That’s indoors, at least.) And then some “free time” / exercise. Followed by dinner. And a couple more roll calls. Then it’s good night, and don’t get caught outdoors in the night, or else… And so on…

It’s the castle yard that is lined with barbed wire fences. There are four watch towers placed around this confined area. And the three barracks in the middle of the yard is where all the prisoners are kept. A part of the ground floor (Seventeen rooms.) of the castle is used for dining, isolation, etc. But the part that ignites the hopes of escaping is the fact that some previous P.O.W.s have attempted to tunnel their way out of the camp. There is a concealed tunnel entrance in one of the barracks, but to figure out where the tunnel leads – That is up to you. This obviously has to be done during the hours when the guards think that you’re sleeping. And you won’t get very far without the proper equipment, like some sort of light source is good to have down in the pitch dark underground.

The Great Escape is loosely based on the John Sturges movie from 1963, and the game is an isometric view four-way scrolling arcade adventure with not as much of the “arcade” elements than regular puzzle solving. The controls are easy enough. You walk around and pick up / drop objects (Fire-button followed by Up / Down on the Joystick / keyboard respectively.), and use said objects (Fire-button in combination with Left or Right.) in their right places. On screen is your morale indicator (A two-frame animated vertically moving green / red flag on the ZX Spectrum-version and a simple percentage value on the C64-one.), an alarm bell, your two-item inventory, and score. (The score counter looks much better on the Speccy with medals as decorations.) When the alarm bell sounds, it’s followed by the objective, e.g., “Roll call”, and that’s when you have to be in the right place as soon as possible. Missing head counts decreases your morale. The same happens if you get caught in places where you’re not supposed to be. This is followed by some time in solitary confinement. When the morale is zero, you turn into the camp’s most obedient prisoner and can’t control the character anymore. (That’s pretty much similar to Game Over.) Following the rules increases the morale just like finding good stuff in Red Cross parcels and making progress with your escape plans. (On the Spectrum-version, the morale flag turns red when you’re doing something that might get your ass thrown into the isolation cell.)

The camp is also populated by the guards and Der Kommendant. The guards have their schedules and follow their objectives like clockwork, but the Kommendant is an unpredictable bastard and can show up where and when you least expect it. During the night, searchlights scan the yard for any suspicious movements. (And it’s never a good idea to try to run away from the guards.) But your fellow P.O.W.s can also be of some help when you need something that distracts the guards. As you can’t carry more than two items, you need a safe place for your stash. (When you’re arrested, the guards immediately take everything that you have “borrowed”.) You will need around ten items to be able to escape and make it on the other side. All the characters in the game move independently, and if you let go of the Joystick and don’t touch it for a few moments, your character returns to the strict schedule of the camp. It’s an effective way to simulate the tediousness. But you can gain control again at any time and get back to the escape plans if you have some morale left. (This also means that you don’t have to walk to the roll calls manually unless you really want to.)

The Great Escape can sort of be seen as a return to form for the Dentons after a very small handful of slightly less sophisticated games. (But not in the least sub par.) This game on the other hand has several advanced and original features, a unique and appealing art-style that kind of reflects a black and white movie (In an alternate dimension 1940s.), interesting and exciting gameplay, and the high overall entertainment quality to match. It should be a delight to discover stuff in the surroundings that “nobody” else has discovered yet. And equipped with a good ability to put yourself into the situation of a prisoner of war, it’s “shit your pants”-exciting to sneak around outdoors and avoiding the beams from the searchlights after lock down… And then, there’s the heartbreak when the guards find your hidden items and the morale just plummets…

The C64-version doesn’t run quite as evenly or well as the Speccy one. The “frames per second”-rate tends to get a bit sluggish on the near single-digit side and a very jittery scrolling follows the drops. This happens usually when several prisoners mingle about on one screen. But it’s nowhere near disastrous, and once you have played the game for a while, you are not really thinking about it too much. And the on screen playing area is significantly larger in the Zed-Ex original. (Approximately 20% or so.)

Okay… And what about the sound in The Great Escape? You might remember that I mentioned the alarm bell sounding? Yep – That’s about it. So this is like a video game version of a near-silent movie.

The C64-version port was coded by Trevor Inns. (Who also programmed Bobby Bearing and Fairlight – A Prelude.) The two versions were also released several months apart. (Problems with the conversion, maybe? Or somewhere else?) — Release: (ZX) Fall (October) 1986 / (C64) Summer (July) 1987 · Credits: (ZX) John Heap, Ally Noble / (C64) Trevor Inns, Steve Wahid · ZX Spectrum 48K (Cassette) / Commodore 64 (Cassette)

Note: Also released for Amstrad CPC, MS-DOS, and a handful of other platforms.

(To be continued…)